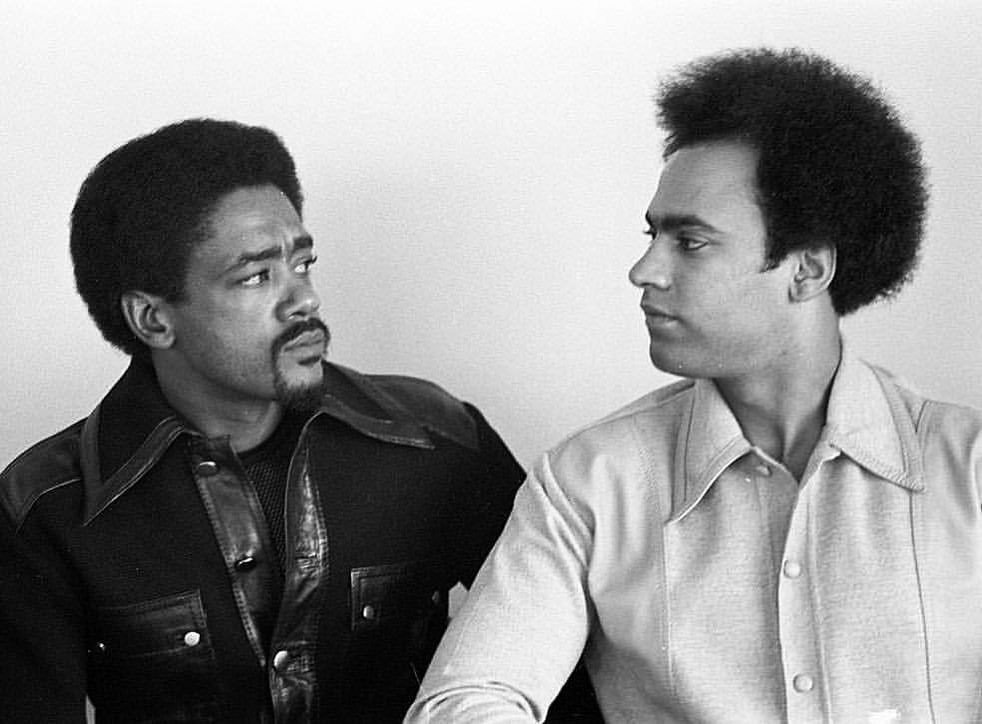

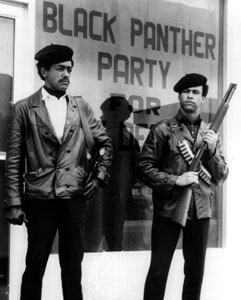

Oct. 15, 1966: 55 years ago, Oct 15 1966, Huey P. Newton & Bobby Seale, radical [...]

55 years ago, Oct 15 1966, Huey P. Newton & Bobby Seale, radical students at Oakland’s Merritt College formed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Inspired by SNCC’s Lowndes County Freedom Organization, the BPP would have an enormous impact on global revolutionary politics

While they quickly made a major impact on the American political scene, the BPP didn’t come out of nowhere. The mid-’60s Oakland they emerged from was swirling with Black radical organizations, thinkers, and militants which they worked with, learned from, imitated, and critiqued

Specifically, Newton & Seale were profoundly influenced by the politics & rhetoric of the Revolutionary Action Movement, a pioneering Black Maoist group, and the community organizing tactics of the Oakland Direct Action Committee, a militant civil rights group led by Mark Comfort

RAM began in 1962 as a study group in Philadelphia (with roots in an Ohio chapter of SDS). Inspired by Robert F. Williams, an NAACP leader who was exiled to Cuba after advocating armed Black self-defense, they promoted the idea of revolutionary urban guerrilla warfare

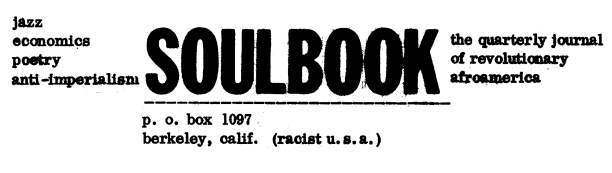

The Oakland RAM chapter founded a student group at Merritt College called the Soul Students Advisory Council, with which Newton & Seale became involved. In 1965 Seale became the distribution manager for RAM’s Berkeley-based theory and poetry journal Soulbook

Much of the analysis which later became synonymous with the BPP (the combination of militant Black nationalism with revolutionary internationalism, along with a strong emphasis on armed insurrection) was developed by RAM and can be found in the pages of Soulbook

At the same time, another major current of Black radicalism in Oakland emphasized practical activity over theory. The Oakland Direct Action Committee formed out of the collapse of the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination, an early civil rights group https://t.co/j353cuV4p5

ODAC was led by Curtis Lee Baker (the “Black Jesus of West Oakland”) and Mark Comfort. As a young man, Comfort was trained as an organizer by the Communist Party’s Roscoe Proctor, after a CP campaign saved him from a lengthy jail sentence for defending himself from a white racist

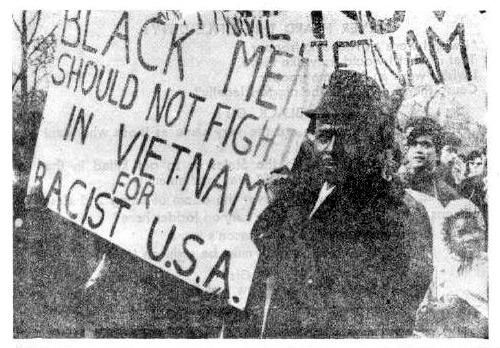

ODAC turned away from organizing students (although they maintained very close ties to the student left in Berkeley) and towards organizing Black working class youths. ODAC organized street gangs in East Oakland to protest police brutality while agitating for jobs and against war

In what would serve as a direct inspiration to the BPP, ODAC also performed police patrols, following cops and monitoring their behavior. When ODAC witnessed a person being unjustly arrested, they would accompany them to the police station and pay their bail

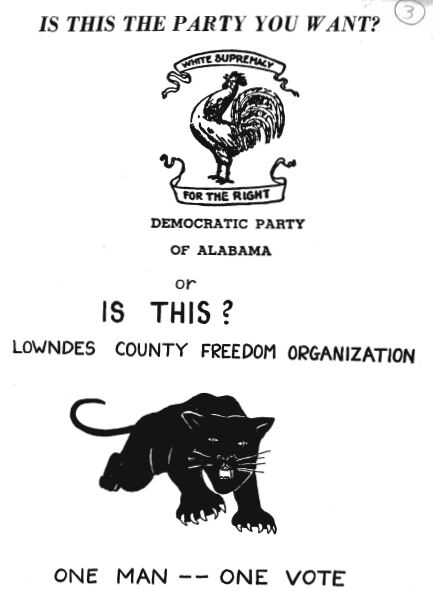

In 1965, Comfort led a West Coast delegation to Lowndes County, Alabama to support SNCC’s efforts to form an independent political party to represent the interests of the Black population. Called the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, it became known as the Black Panther Party

Inspired by what he had seen in Lowndes, Comfort asked SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) for permission to start a Black Panther Party in California, to which Carmichael replied: “It’s the people’s. We ain’t got a patent… If local conditions indicate, go for it.”

In Oakland, Comfort worked to spread the Panther name and symbol. According to Ture, by late 1966, 10 to 12 groups were using the name in California, along with groups in Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago. An attempt by Carmichael to merge these groups in Oakland failed

Around this time, frustrated with RAM’s “armchair intellectual” inaction, Newton & Seale performed an ODAC-style police patrol, using SSAC money to bail out a Black man whom they had seen be harassed by police. After this resulted in a reprimand from SSAC leadership, the two quit

Shortly thereafter, Newton & Seale borrowed the Black Panther Party name & symbol, ODAC’s police patrols (to which they added guns), RAM’s revolutionary rhetoric & analysis, and Mark Comfort’s signature black berets, creating the Bay Area’s best-known revolutionary group