‘Bodies and force’: Lessons from Alameda’s tenant organizers of the 1960s

By Matt Ray, Matt Wranovics // May 8, 2024

Lessons from Alameda’s tenant organizers of the 1960s.

Originally published by Street Spirit.

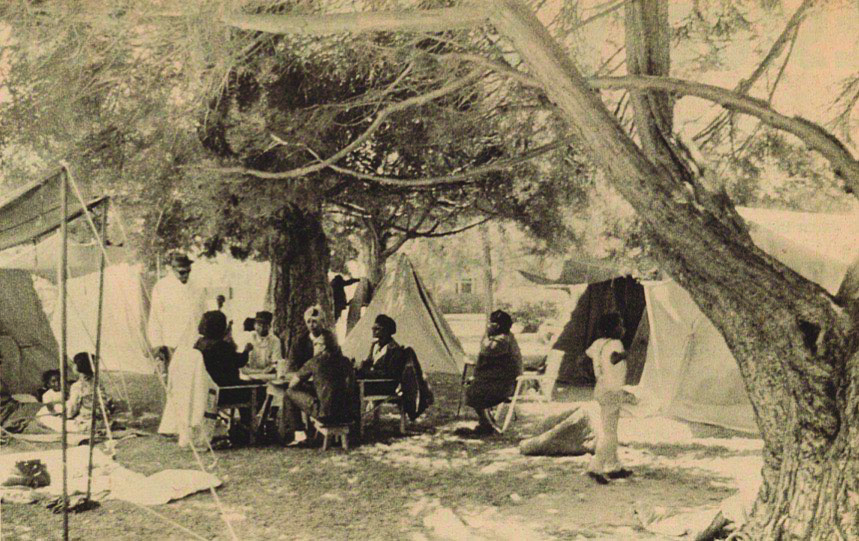

Estuary tenants and members of the Citizens’ Committee for Low-Income Housing set up camp in Alameda’s Franklin Park to protest their eviction from the housing project, as well as racist practices by the Alameda Housing Authority. (Lynn Phipps/The Flatlands newspaper – July 2, 1966)

“To hell with the Alameda Police Department!” Mabel Tatem declared to her neighbors as they huddled in Franklin Park.

Mrs. Tatem was a resident of the nearly all-Black Estuary Housing Project, and president of the Citizens’ Committee for Low-Income Housing. She and her fellow Estuary tenants had been served an eviction notice. It’s 1966, and to show local authorities they meant business, the tenants had set up camp in a public park in Alameda’s wealthy, White Gold Coast neighborhood.

“If they come in here and start to take out anybody or move anybody’s furniture… we’ll move it back in, sayin’ take it out and you’ll have to come through us. And I mean have it hard and heavy.”

Until World War II, Alameda was a small city with an even smaller Black population. That all changed when the Navy commissioned Naval Air Station (NAS) Alameda in 1940. Thousands of people poured in to work in the war industry, among them were large numbers of African-American workers from the South. These workers found a rigidly segregated city with a massive housing shortage, and many had no choice but to move into the temporary housing projects the federal government hastily constructed on Alameda’s West End in 1943. These projects, too, were starkly segregated, with White and Black residents forced onto separate blocks. They were managed by the Alameda Housing Authority, a new agency staffed entirely by representatives of the city’s business elite and chaired by Fred Zecher, a local banker who openly used the n-word in front of reporters to refer to his own tenants.

After the war, kicking Black people and other poor project dwellers out of Alameda was at the top of the AHA’s agenda. The projects faced their first threat of demolition in 1950. The worst was avoided, in part, thanks to organizing by the communist-led Committee to Save the Housing Projects (Alameda was home to four Communist Party clubs in this period, with a strong base in Alameda’s Black community). But over the following decade, the projects started closing down one-by-one. No new housing was provided for displaced tenants, who were simply thrown out on the street. A combination of high rents and racist landlords forced many out of Alameda altogether. While the “temporary” pressboard and plywood housing projects were dirty, neglected, and dangerously unmaintained, residents simply had nowhere else to go. By the end of the 1950s, Alameda lost nearly half its Black population.

When eviction notices hit Estuary in 1963, tenants resolved not to go down without a fight. They got organized, forming the Citizens’ Committee for Low-Income Housing with help from the NAACP and a fair housing group called HOPE. In response, the AHA set about making life in the project as miserable as possible, hoping residents would evict themselves. They removed mailboxes and garbage disposals, shut down laundry and bus services, and harassed people in all kinds of imaginative ways. Undaunted, the committee executed a series of escalating actions, beginning with protest marches and culminating in a multi-day school boycott. Shaken, authorities responded by delaying the evictions and demolition but steadfastly maintained they would not provide new housing. “It is not our obligation,” Chairman Zecher insisted.

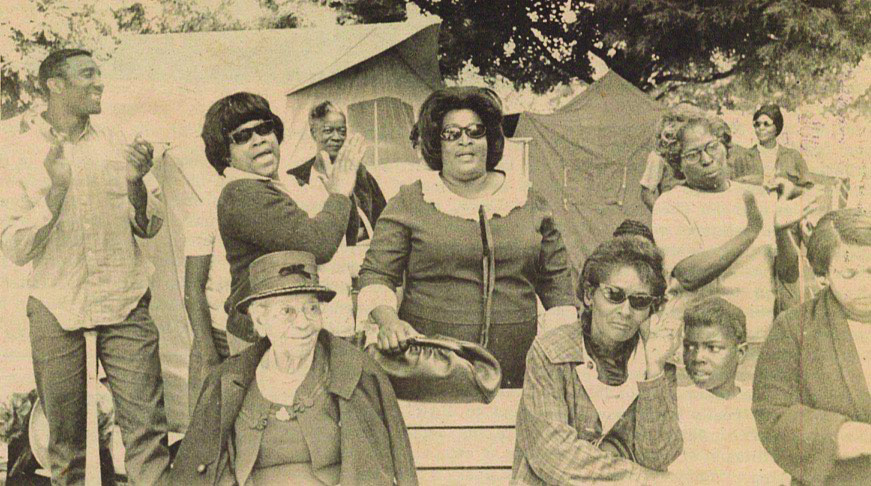

Tenants of Estuary Housing Project camp out at Franklin Park. (Lynn Phipps/The Flatlands newspaper – July 2, 1966)

Defying a legal prohibition against selling the property to a for-profit entity, the AHA exploited a loophole in late 1964 to sell the Estuary land to a company called Moscini & Cristofi, which incorporated a non-existent church to operate as a front. Meanwhile, with the Vietnam War ramping up in the background—in which Mabel Tatem’s husband was fighting—the military regained interest in the site. Moscini & Cristofi cut a deal with the Navy, selling them the land in exchange for the Navy-owned Savo Island Housing Project in Berkeley, which they hoped to rent as apartments. (This didn’t go as planned; their new tenants quickly organized against a draconian crackdown on keeping dogs, and the next year, Berkeley radicals briefly took the site over with the help of the Black Panther Party).

Refusing to back down from their demand for guaranteed housing, hundreds of Estuary tenants and their supporters marched through the all-White Gold Coast neighborhood in June 1966. After stopping briefly to protest outside Mayor Godfrey’s house, they marched all the way to Franklin Park and proceeded to set up camp. In anticipation of their arrival, the Alameda Fire Department sprayed the park with fire hoses. Despite the mud—and a few hecklers setting off cherry bombs—the Estuary tenants quickly made the park their own, announcing they would not leave until their demands were met.

Participants in the “tent-in” described a joyous “summer camp” atmosphere. “The children are really enjoying themselves,” explained camper Dorothy Reed, “it’s the first time they have a park to play in all day…. It’s better living here than in the projects.”

Support for the tent-in poured in from local civil rights groups and churches. Clergy from across the East Bay, White and Black, came to Franklin Park and offered to hold an interfaith service for the campers. “God is with us,” exclaimed Mrs. Tatem, “People are coming from all over to help us fight. I could cry like a baby, but being a mature woman I am too hard core for that.”

While they faced predictable hostility from the police, who patrolled the park frequently, the tenants were surprised by their warm reception from Gold Coast families, few of whom had even been aware of Estuary’s existence, let alone the conditions there.

As the pressure mounted, the city government’s once-intransigent attitude began to soften. At a City Council meeting held during the action, Alameda NAACP president Clarence Gilmore told the council, “These people are going to live in decent housing or in tents or jails—you will decide which.” Oakland-based Black Power leader Curtis Lee Baker was even more direct, telling the politicians, “What I think of White bigots and pigs and dogs and Uncle Toms and Aunt Jennys is nothing. If you don’t mediate this problem you better build up your police department… It is time for you to take humanity’s responsibilities.” Six days after Estuary tenants first pitched their tents, the mayor caved to their principle demand, accepting responsibility for providing tenants with new, low-cost housing. The committee’s more ambitious demands, including the replacement of AHA chairman Zecher by one of their own members, were not met. When asked what changed Mayor Godfrey’s attitude, Mabel Tatem replied: “Bodies and force.”

Of course, the story didn’t end here. Unsurprisingly, the government was slow to fulfill their promise. Rather than build new housing, the city moved many Estuary tenants into the majority-White Makassar Village Housing Project, which had earlier been strictly reserved for Navy families. At Makassar, tenants dealt with many of the same struggles they hoped to leave behind at Estuary. In 1976, five years after Estuary was finally demolished, the now-majority Black and Filipino Makassar residents organized a tenants union to combat another impending demolition. Like Mabel Tatem and her neighbors in the 1960s, they won some fights and lost others. The project eventually came down in 1981. While far from total, Estuary tenants’ victory in summer 1966 reminds us what exploited people can accomplish when they confront their situations with determination, creativity, and solidarity; bodies and force.

Matt Ray

Matt Ray is a founder of Left in the Bay.

Matt Wranovics

Matt Wranovics is a founder of Left in the Bay.